WET PLANTS ARE THERE FOR A REASON

Zoltan is surrounded by tins of raw corn and fly larvae, cans of Borsodi beer, and his Trabant playing Hungarian hits from the 70s. He feels at one with nature, nestled at the side of Malom Tó (lake), happily watching ducks skim the surface.

Two hours of calm waiting, then a tug on his translucent line drives him to his rod. The next ten minutes are blessed with pulling the unwilling victim ashore, presenting the

33 cm grass carp to envious friends, throwing him back in, and opening a fresh Borsodi. The fish also returns to what it was doing - eating. Grass carp, an alien species from Asia, were introduced to Malom Lake in the 1970s because of their appetites - they can eat their own weight in vegetation daily. Requests for the fish had come from local fishing associations to clear the lake of reed-grass vegetation to allow more space for fishing and rowing. In record time, the foreigners ate just about everything. "Fish like grass carp are added to about fifty percent of the 1,000 small lakes in Hungary," says Sándor Tatár, a representative of the local NGO Tavirozsa. "The result is that nearly half of the lakes have been virtually cleared of vegetation."

33 cm grass carp to envious friends, throwing him back in, and opening a fresh Borsodi. The fish also returns to what it was doing - eating. Grass carp, an alien species from Asia, were introduced to Malom Lake in the 1970s because of their appetites - they can eat their own weight in vegetation daily. Requests for the fish had come from local fishing associations to clear the lake of reed-grass vegetation to allow more space for fishing and rowing. In record time, the foreigners ate just about everything. "Fish like grass carp are added to about fifty percent of the 1,000 small lakes in Hungary," says Sándor Tatár, a representative of the local NGO Tavirozsa. "The result is that nearly half of the lakes have been virtually cleared of vegetation."

The fish's impacts on Malom Lake were too much on top of earlier impacts. From the 1920s, landscaping and dredging to make way for new housing developments destroyed large areas of plant life. Waste cesspits were also dug that leached pollution into the groundwater and lake. Nutrient pollution increased but the ecosystem could handle it given the ability of the remaining lake plants to absorb pollution. "But once the grass carp started eating, the lake's self-cleaning capacity ended and nutrient pollution skyrocketed," says Tatár. By 1980, large algal blooms appeared. Water quality deteriorated and fish reproduction decreased. The area's rare and endangered plants were also hit. In the 1980s, for example, lápi rence reed-grass, a fantastic plant that eats aquatic insects with its underwater leaves, completely disappeared. Now strictly protected in Hungary, the plant used to attract botanists from across the country to Malom Lake. In 1985, Malom Lake was given national protection status. Even though adding foreign fish species became prohibited by law, fishing associations continued to stock the lake with grass carp. In 1996, a new sewage treatment plant was built near the lake for the local town of Veresegyház and neighbouring villages. Plant capacity was over-used, however, to the point that concentrations of nutrients discharged from the treatment plant were above permitted levels and leached into the lake system. Bacteria levels increased sharply including toxic cyanobacteria and coliform bacteria resulting in human symptoms such as allergic reactions, fever and vomiting. "Water quality at the sand beach became catastrophic," says Tatár. Having attracted some 3000 to 4000 people daily in the past, beach numbers went down by ninety percent after 1990.

TAVIROZSA FOUNDED

In response, some local residents united to form the Tavirózsa NGO in 1996. With funding from the Hungarian government, the NGO assessed local water quality and biological factors in the lake and surrounding Szödrákosi-patak (creek) catchment area of 132 sq km. The creek runs north through Veresegyház and its three lakes including Malom Lake before draining into the Danube River above Budapest. Natural, social and economic values, protected species and human impacts were also assessed. Early successes included discoveries of protected areas that had been illegally cut or drained and gaining protection status for another valuable area. Discussions with the Mayor led to a plan to upgrade the local treatment plant to remove nutrients, although a lack of funds could delay works. In 2006, with help from the UNDP-GEF Danube Regional Project (DRP) Small Grants Programme, Tavirozsa purchased equipment to test water in three lakes. Monitoring found that big rains in April and May caused significant nutrient pollution to the lakes because of the city's poorly combined sewage system. In one instance, rain volumes pushed up the solid steel cover of a sewer allowing sewage to seep into the lake. The NGO notified local and regional authorities who came to test the water themselves. "But they didn't test bacteria or algae," says Tatár.

In early August, Tavirozsa measured algae and cyanobacteria chlorophyll and found counts to be double acceptable limits. Tatar notified the Hungarian health authority (ANTSZ) but they didn't answer promptly. By August 18, the NGO measured counts four times the accepted government limit. ANTSZ finally did appear on the scene, but only at the end of the bathing season, and they also failed to measure all parameters as required by law, says Tatár. "The government didn't want to send out bad news during top season," says Tatár.

In early August, Tavirozsa measured algae and cyanobacteria chlorophyll and found counts to be double acceptable limits. Tatar notified the Hungarian health authority (ANTSZ) but they didn't answer promptly. By August 18, the NGO measured counts four times the accepted government limit. ANTSZ finally did appear on the scene, but only at the end of the bathing season, and they also failed to measure all parameters as required by law, says Tatár. "The government didn't want to send out bad news during top season," says Tatár.

Interestingly, Veresegyház, not long ago a village, is one of the fastest growing cities in Hungary, attracting some 500 new residents a year to a new suburb 30 minutes from busy Budapest, current population 13,000. The fishing lakes, beach, wetlands, all-year thermal bath and even a bear sanctuary draw new people from Budapest. Taking matters into their own hands, the NGO has since created Tavirozsa Radio (www.tavirozsa-radio.hu, FM 107.3), the city's first radio station, to raise public awareness. And in the recent Hungarian October local elections, Tatár became a local councillor in Veresegyház.

GOODBYE GRASS CARP, HELLO REED-GRASS

DRP funds were also used by the NGO to implement a demonstration wetland rehabilitation project at the top end of one of the city's three lakes, Pamut Lake.

"We support the project because it will bring the reed-grass back which will help bring back some valuable local fish species that have almost disappeared," said the leader of Pamut Lake's fishing association's, Gusztáv Kiss. "Water quality will improve. Grass carp won't be added to our lake anymore." Following a baseline environmental assessment in the spring of 2006, the small lake area was fenced off and all grass carp were removed. Rooted and floating native reed-grass with high nutrient removal capacities were collected from nearby lakes in bags and then manually added to the site. "We are confident that the new reed-grass will help improve water

quality and fish habitat," says Tatár. He then brings me to a small highly vegetated wetland area with a small link to Malom Lake.

Pulling out a floating needle-like coontail plant, he says that, because the plants here have been able to remain healthy, water quality is two grades higher than that in algae-green Malom Lake and "the water is full of life". The next step is to test the demonstration site water in the future to prove that quality improved. Based on that evidence, Tatár hopes to secure a larger project using the same strategy to restore all three lakes starting in 2007. "It's a good idea to have all three lakes included," says Kiss. "Grass carp might return to our lake otherwise, for example carried over by birds." Tatár also wants to ensure that pollution from the local treatment plant stops soon. "With small funds, one can improve the natural self-cleaning capacity of wetland areas," he says. "The bigger problem is getting local support. At Pamut Lake, we were able to convince the fishing association there to accept the project. But the other two lakes each have their own association, and they're not convinced yet. They still prefer their grass carp and open water space to the reed-grass, clean water, clean beach and healthy ecosystem. Now we're working to change their perceptions."

Pulling out a floating needle-like coontail plant, he says that, because the plants here have been able to remain healthy, water quality is two grades higher than that in algae-green Malom Lake and "the water is full of life". The next step is to test the demonstration site water in the future to prove that quality improved. Based on that evidence, Tatár hopes to secure a larger project using the same strategy to restore all three lakes starting in 2007. "It's a good idea to have all three lakes included," says Kiss. "Grass carp might return to our lake otherwise, for example carried over by birds." Tatár also wants to ensure that pollution from the local treatment plant stops soon. "With small funds, one can improve the natural self-cleaning capacity of wetland areas," he says. "The bigger problem is getting local support. At Pamut Lake, we were able to convince the fishing association there to accept the project. But the other two lakes each have their own association, and they're not convinced yet. They still prefer their grass carp and open water space to the reed-grass, clean water, clean beach and healthy ecosystem. Now we're working to change their perceptions."

Tatár also hopes to increase national and international awareness of their efforts at Malom Lake. "It's a small lake but it's connected to the Danube. The issues surrounding wetlands and alien species are basin-wide." Funding from the UNDP-GEF DRP for Tavirozsa's project is just one among many activities being funded across the Danube River Basin to protect and restore wetlands, and to raise the importance of wetland management in river basin management. Besides funding NGOs in other Danube countries, examples of other DRP wetland-related activities include raising awareness of the importance of wetlands among Slovak water managers, and assessing the effectiveness of wetlands in reducing nutrient pollution.

Tatár also hopes to increase national and international awareness of their efforts at Malom Lake. "It's a small lake but it's connected to the Danube. The issues surrounding wetlands and alien species are basin-wide." Funding from the UNDP-GEF DRP for Tavirozsa's project is just one among many activities being funded across the Danube River Basin to protect and restore wetlands, and to raise the importance of wetland management in river basin management. Besides funding NGOs in other Danube countries, examples of other DRP wetland-related activities include raising awareness of the importance of wetlands among Slovak water managers, and assessing the effectiveness of wetlands in reducing nutrient pollution.

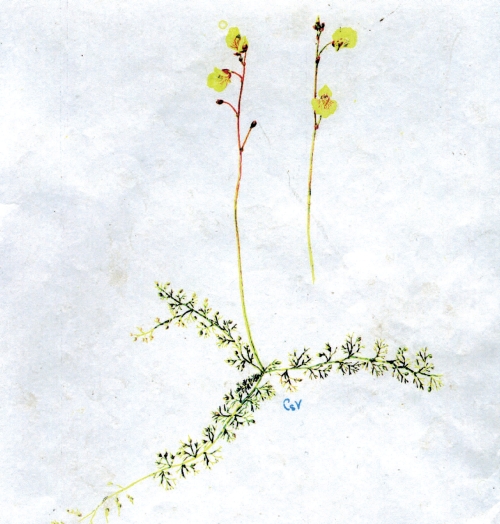

The extinct Utricularia bremii

Aquarell painted by Vera Csapody in Veresegyház, 1947

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT DANUBE REGIONAL PROJECT PLEASE CONTACT:

DRP: Paul Csagoly, Communications Expert, Vienna International Centre D0437, P.O. Box 500, A-1400, Vienna, Austria. (tel) +43 1 26060 4722. (mob) +43 664 561 2192,

paul.csagoly@unvienna.org

DRP: Peter Whalley, Envirnomental Specialist, Vienna International Centre D0437, P.O. Box 500, A-1400, Vienna, Austria. (tel) +43 1 26060 4023.

peter.whalley@unvienna.org

Download here this Background Story on Wetlands.